Have you ever listened to jazz or blues and questioned why it sounds so different from other genres? One of the reasons why is because this music is played with a swing feel. What is a swing and how to use it in music? Learn it in this guide!

Swing is so prevalent in jazz that a whole subgenre cropped up named swing within the 1930s—typically consisting of massive orchestral jazz bands that played up-tempo ballads.

However, swing as a rhythmic concept has grown effectively beyond its early-jazz roots—if you listen carefully, tons of modern music like hip-hop and R&B make use of swing rhythms.

Today modern producers obsess over DAW swing settings and idolize beat-making pioneers like J Dilla who utilized electronic tools to make electronic variations of swing.

If you want to add a little bit of skip to your beats and make tracks that’ll get your audience’s heads bobbing–you may want to incorporate a bit of swing into your music.

In this article, we’ll learn about the music theory and history behind swing rhythms. And we’ll discover a couple of ways you should use swing in your songwriting.

Let’s dive in!

What is swing?

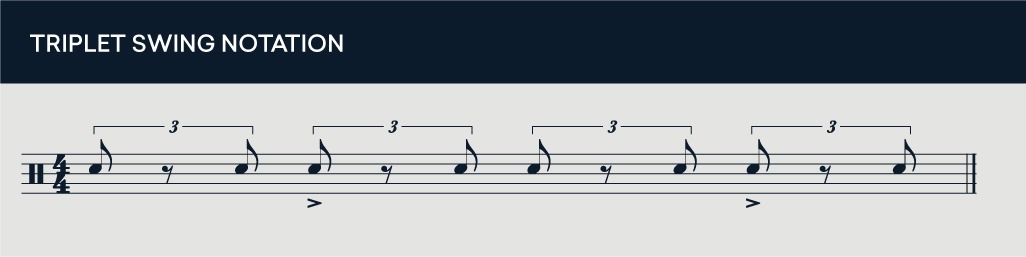

In music, swing refers to a particular way of interpreting rhythm where eight notes are performed like triplets to create a galloping sound. Swing also refers to a style of early jazz music that heavily used this style of rhythm.

Swing and jazz are deeply related—jazz artists from the 1930s coined the term and most jazz from the 1930s up until the 1970s was exclusively played using a swing feel—that features everything from traditional New Orleans jazz to be-bop.

The theory of swing music

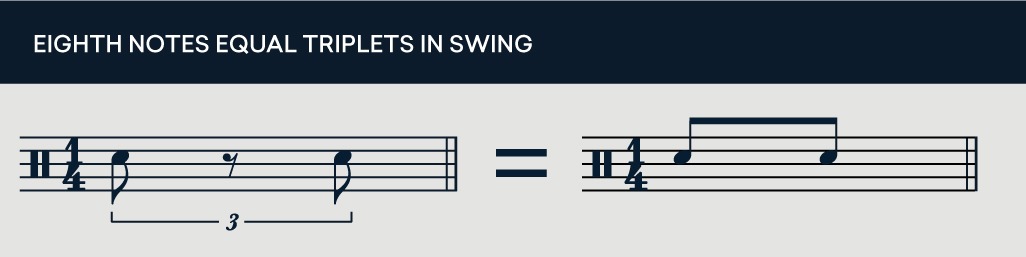

To understand swing, it’s essential to understand a bit about music theory—particularly the difference between eighth notes and eighth note triplets.

That’s because swung rhythms are written in music notation as eighth notes. However, in reality, they’re played as though they’re triplets with a rest in the middle.

Essentially, the music notation draws an equivalency between these methods of writing a swung rhythm.

Swing emphasizes the backbeat

There’s a bit more to swing it than just that- Beethoven’s 9th symphony used very similar rhythms that were notated as eighth note triplets. This music will not be considered to be swung.

These triplets were performed more like a dotted eighth note barred with a sixteenth note. It’s a subtle difference, but if you listen to the way Beethoven’s 9th gallops. It’s a special feeling that doesn’t swing.

Movement two from Symphony No.9 is an effective example of this phenomenon. Listen carefully to how straight the orchestra plays its triplets.

There’s a difference in timing between how an orchestra plays and feels a triplet, especially when the middle note gets a rest, versus the best way a jazz player will play a set of swung eighth notes.

This difference in feel is due partly to variations in articulation that jazz players use and its heavy emphasis on the backbeat—an accent falling on the two and four—that jazz music is famous for.

Classical music emphasizes the one and three counts of a 4/4 measure. So, it;’s impossible to swing since the rolling, galloping feel of swung music naturally emphasizes the two and four.

Swing feel is an artistic decision

Truthfully swung rhythm defies music theory, in that you can’t notate it properly on the sheet.

True to its rebellious, “low-brow” roots, the way a musician plays swing actually is a creative choice.

When you develop an ear for hearing swing in a piece of music, you’ll discover how different drummers play swing differently by moving the emphasis and timing of the eighth notes around.

Jazz drumming legend, Art Blakely puts on a masterclass of swing music in his bluesy track Moanin’. His drumming embodies a more classic swing feel with evenly spaced eighth notes that match perfectly into a swung pattern.

However other drummers honed their sound and style of playing swing.

Elvin Jones, for instance, is famous for having a very tight swing feel—often playing the off-beat quarter notes slightly late and closer to a sixteenth note.

Elvin’s swing style is a little more jarring and sounds like nearly straight sixteenth notes—almost like Beethoven!

If that’s confusing, just listen to his track “Half and Half” and compare it to “Moanin”—both tunes are performed swung. However, the two drummers sound completely different.

Playing “in the cracks”

This phenomenon of playing around with the timing of swing rhythms was found and pioneered during the be-bop and hard-bop era of jazz music.

Drummers, like Elvin Jones, who perfected a particular swing feel, somewhere between fully swung and fully straight was described as playing “in-the-cracks”.

This is term producers and artists use today to explain a particular way of playing.

Playing “in-the-cracks” means the swing feel is performed somewhere between a triplet and an eighth note.

So an in-the-cracks groove will rhythmically fall somewhere between the above methods of taking part in within two-quarter notes.

If you ask a drummer to play more within the cracks, you’re asking the drummer to adjust their playing to be somewhere between swung and straight–a skill that many drummers will spend tons of time if not entire careers perfecting.

In-the-cracks and hip-hop

Producers like J Dilla and modern drummers like Chris Dave and Karriem Riggins took inspiration from these jazz drumming roots and re-invented the hip-hop feel.

Dilla was a master at putting hip-hop rhythms “in-the-cracks” to create a genre-pioneering model of hip-hop beat making.

Riggins and Dave are masters of that Dilla-Esque feel that took well-known hip-hop grooves and twisted them with off-time, “in-the-cracks” snare hits that also sound somewhat robotic and straight.

It’s a tremendous line to discover a swing feel that sounds good. But today’s jazz drummer is spending time perfecting this new modern way of feeling swing and hip-hop grooves.

Listen to have Dave is consistently playing around the beat. He’s the reason why I say drummers turn their variations on a swing into an artistic choice.