Rhythm is one of the fundamental aspects of music theory.

To make great harmonies and melodies you should know how rhythm works and how it is used in your tracks.

Rhythm can get difficult very quickly, but if you learn a few simple concepts it’s not as hard to understand as you may think.

In this guide, we’ll unpack everything you need to know about rhythm and start applying rhythmic or polyrhythmic concepts in your creative process.

You’ll know how we subdivide rhythms in music, how time signatures work, and how to begin understanding compound and odd time.

What is Rhythm?

Rhythm is the way that we can systematically divide music is into beats that repeat a specific number of times within a bar at a collectively understood speed or tempo.

Rhythm is how musicians connect and interact with one another.

At least, that’s the definition you would get if you asked a metronome.

Rhythm is pretty hard to define. It’s what makes music, music.

Notes, melody, and chords can be easily described as vibrations in the airwaves that our eardrums can detect.

Rhythm has more to do with your uniquely human perception of time.

If you asked someone in a drum circle they would probably tell you rhythm is about playing together.

You should ask a funk band then they’ll tell you rhythm is about finding a groove.

Neither of those answers is wrong because rhythm is how musicians connect and play with one another.

Rhythm theory: understanding what’s on the page

For our purposes, we’ll look at the western way of understanding rhythm.

To understand rhythm, there are four basic concepts to know:

- Beats and notes

- Measures and time signatures

- Strong and Weak Beats

- Double and Triple Meter

When you master these four concepts you’ll be able to practice better and you’ll get better at using interesting rhythms in your tracks.

1. Beats and notes

There’s a lot to go through when it comes to understanding how to read musical rhythms.

But the most important thing of feeling any rhythm, you have to understand that a musical note represents the duration of time that an instrument will be played.

A musical note represents the duration of time that an instrument will be played.

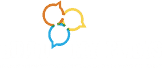

A whole note represents the longest playing duration but whole notes can be broken down into halves, quarters, eighths, and sixteenths.

A half note will occupy half the duration of a whole note. A quarter note will occupy a quarter of the duration of a whole note and so forth.

There are many ways to represent different rhythms by changing and organizing these notes.

But as a foundation for how visually and conceptually understand rhythm in music your first step is to know how notes are broken down.

2. Time signatures and bars

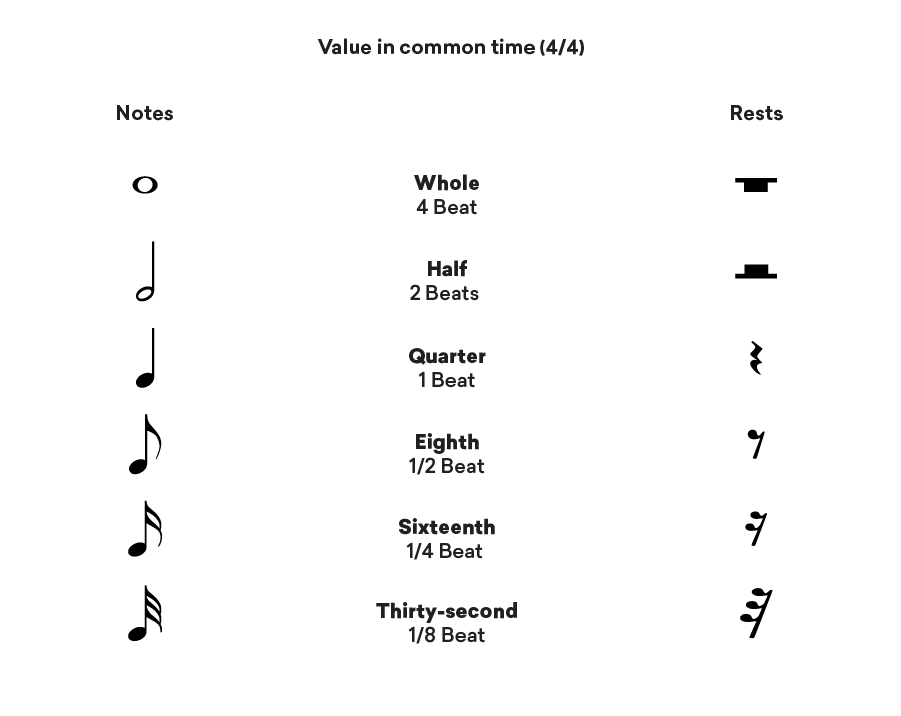

There is an underlying pulse in all music that can be contained within a specific measure of time.

This measure of time is referred to as a musical bar or measure.

In western music, the time signature of a song dictates how to measure its pulse in each bar and tempo defines how fast the pulse is.

The pulse is represented by a fraction-like symbol that dictates the number of notes per bar and how to count each note in terms of halves, quarters, or sixteenths.

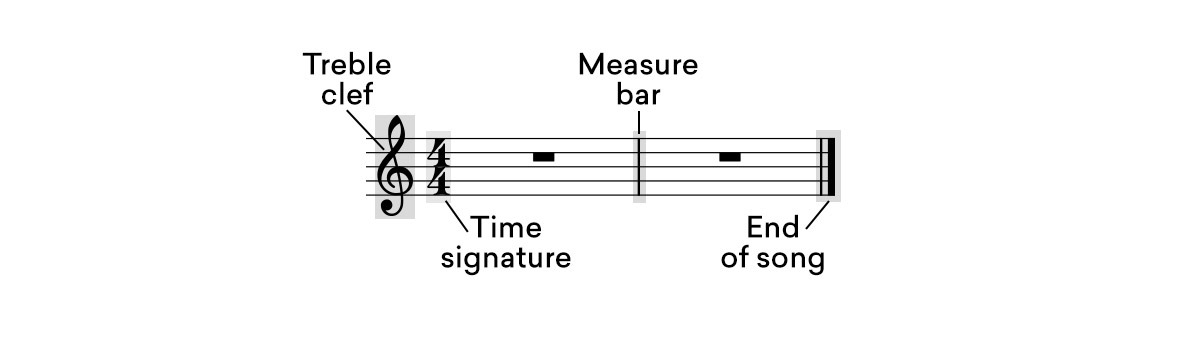

Consider the most common time signature in music– 4/4.

The number four on top says that there are four pulses to one bar. The number four on the bottom says that we can measure these pulses in terms of quarter notes.

Of course, there are many time signatures in music beyond 4/4.

Every waltz you’ve ever heard is in 3/4 and then there’s the world of a compound and odd time.

3. Strong and weak beats

Now you know the way time signatures work and how beats fit into a bar, let’s look at how rhythm works within a bar.

Within a bar, there are strong beats that drive the pulse and there are weak beats that counteract the pulse.

Within a bar, there are strong beats that drive the pulse and there are weak beats that counteract the pulse.

This push and pull is what adds definition to a measure and makes rhythms easier to hear.

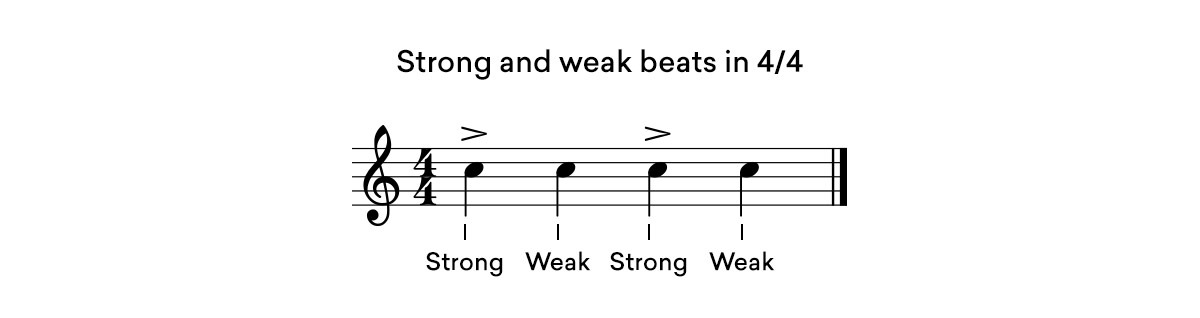

If we consider the common 4/4 measure, the strong beats fall on the first and third quarter notes in the bar and the weak beats fall on the second and fourth quarter notes.

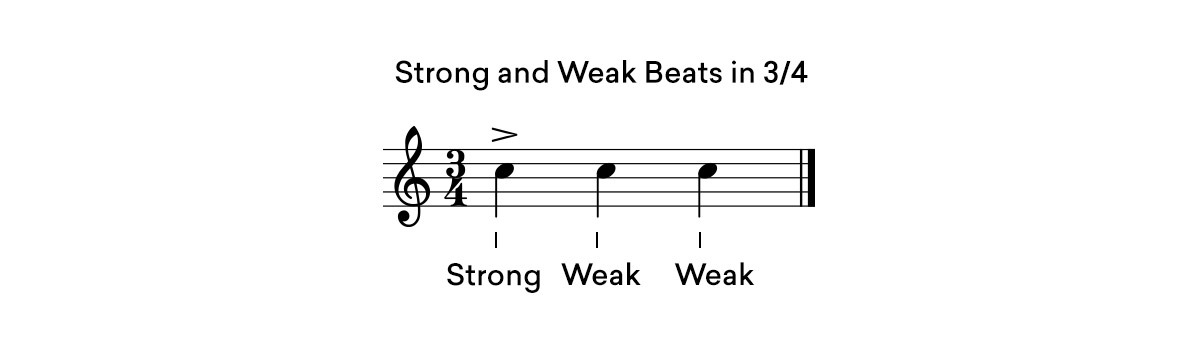

In a 3/4 measure, the strong beat falls on the first quarter note. The weak beats fall on the second and third.

Once you know how beats sound in a musical measure you can hear them everywhere.

The pushing ONE-two, ONE-two pulse of a kick drum on a 4/4 disco track or the lilting ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three in a waltz for example.

The strong-weak, strong-weak-weak concept is part of how duple and triple meter work. They form the basis for understanding compound and odd time.